A Peckham trial

Until the early 1890s Charles Joseph Walls appears to have led a fairly ordinary life. He was born in late 1861 in Ilkley, Yorkshire, one of ten children to Frederick Walls, a stockbroker, and his wife Maria. By 1867 the family had moved to 18 Fawcett Street, Kensington (1871 Census) and by 1878 (1881 Census) across the river to 16 Heaton Villas, Peckham in the parish of St Antholin. Charles, aged 19, was a solicitor’s general clerk.

At the unusually late age of 22 Charles was baptised at All Saints Church, Lower Marsh, Lambeth on 2 March 1884. This was a ‘conditional baptism’ – normally administered when there is doubt whether the candidate had previously been baptised – even though both his parents were still alive. Charles, living at 1 Claude Road, Camberwell, was clearly contemplating a career in the church.

On 2 October 1886 Charles, now a theology student at Durham University, married Alice Tompkins in St John the Divine church, Kennington, and moved into her home at 91 Camberwell New Road. A daughter, Gladys Philippa was born in Kennington the following year and baptised on 28 December 1887 in the same church. Charles gained his Licentiate of Theology from Durham University in 1888, was ordained Deacon in 1890, and moved the family to Christ Church, Luton for his first curacy (1888-1891). He was ordained priest in 1888 in Ely Cathedral. A second daughter, Ignatia Clara, was born at 46 Napier Road, Luton in 1891.

By the end of 1891 Charles had moved to Brent Pelham, in Hertfordshire as curate of St Mary the Virgin. A burial record at nearby Furneux Pelham for 9 December 1891 lists C. J. Walls as ‘Curate of Brent Pelham’.

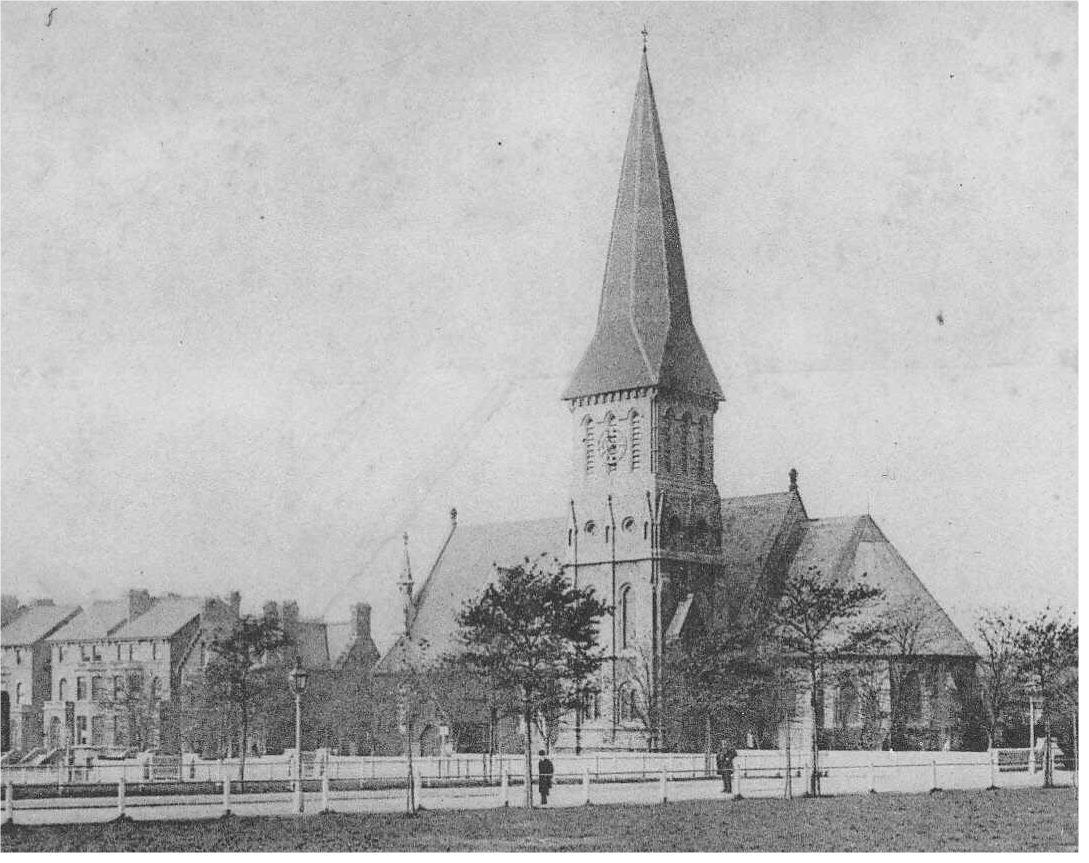

St John the Evangelist, East Dulwich c.1900

Charles next moved to St John’s East Dulwich, then in the Diocese of Rochester, as one of the vicar, St John the Evangelist, East Dulwich c.1900 Dr William J. Strickland’s, team of curates. The entry in the 1894 edition of Crockford’s lists him living at 54 Fenwick Road, Peckham.

Then his life took a strange turn.

In 1894 Charles Joseph Walls was called as a witness for the defence in a rather strange case of begging which cast a shadow on his professional career. Newspapers around the world reported it; The New York Times headlined:

‘Female Fagin at Work in London’. A few weeks later it reached The Melbourne Advocate in Australia as: ‘The bogus nun’. Salacious news in the Victorian era did not need the internet to reach around the world.

The case concerned begging in Putney High Street and obtaining money by false pretences. On Thursday, 13 September Mary Townsend, a nurse, aged forty-four, was brought before Mr Loveland-Loveland, at the London County Sessions, at Newington. Mr Colbeck, prosecuted on behalf of the Treasury. The Guardian summed the case up: ‘It appeared that the prisoner, dressed as a nun, was in the habit of visiting public-houses and collecting subscriptions for the support of two orphanages—one at Peckham and the other at Herne Bay. Generally she had with her a little girl whom she represented as an inmate of one of the orphanages. She also described herself as belonging to the [Guild and] Order of St Charles founded for the purpose of carrying on works of mercy in connection with the Church of England.’ She was still dressed as a Sister of Mercy and claimed she was a sister of the order. The Sisters took the three usual vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. The child was Lily Winter, aged eight.

The Tablet filled in more details: she lived at 42 Elm Grove, Peckham where it was alleged that ‘the Prisoner kept a sort of convent at her house, whither she enticed orphans, whom she used for the purposes of begging. When arrested by Police-constable Norris she stated that she was collecting money on behalf of St Peter’s Orphanage at Herne Bay.’ The South Wales Echo (‘The sham nun’) explained that: ‘The sums of money extracted ranged from 1s to 2s 6d’.

Townsend had claimed that there were thirteen children at Herne Bay and eleven at Peckham. The police investigated the Peckham premises and discovered that it was ‘a private house, poorly furnished, in which there were two little girls only’. St Peter’s Home for Destitute children at Herne Bay did not, and indeed had never, existed.

Townsend had claimed that there were thirteen children at Herne Bay and eleven at Peckham. The police investigated the Peckham premises and discovered that it was ‘a private house, poorly furnished, in which there were two little girls only’. St Peter’s Home for Destitute children at Herne Bay did not, and indeed had never, existed.

Character witnesses were produced for the defence. Mr Edward Townsend said the accused was his mother, a respectable lady and the widow of Dr Townsend who was in practice at Penge for fifty years. The other character witness for the defence was the Rev C. J. Walls. He stated that he was the self-appointed ‘Father Superior’ of the order and that he lived at the house in Peckham. He had been in negotiation with the Vicar at Herne Bay with a view of obtaining suitable premises for a mission home, to be developed into a home for destitute children – but at present it did not exist.

Under cross-examination the Rev Walls’ reputation was publicly shredded:

Mr Torr asked the witness if he had not acted as curate in three different localities, and if he had not left them all in disgrace? The witness replied that he had not.

Mr Torr—Is it true that you were in the vestry for over an hour with a young woman? Witness —No.

Mr Torr—Was a complaint made with reference to a young lady? Witness—Yes, but the vicar was very much in love with the particular young woman. (Laughter.)

Mr Torr—Have not serious charges been made against you? Witness—Yes. So there were serious charges made against the Founder of Christianity; and I, like Him, pay no attention to unfounded charges.

Mr Torr—You had the brokers in, had you not? Witness— Yes.

Mr Torr—Did you go to a public-house with the broker’s man and play billiards with him? Witness—No.

Mr Torr—Did you take a stable in Dulwich and fix up an image of the Virgin Mary, and burn incense in front of the door? No; my acolyte did it.

Mr Torr—Do you owe rent for that stable? Witness—Yes; about.£5.;

By his Lordship—He knew the prisoner had passed under the name of St Clair. Most religious persons took another name upon entering an order.

Further evidence was brought about the unreliability of this witness: his bail for the appearance of the Prisoner had been refused as his licence had been revoked by the Bishop of Rochester on the grounds of ‘ritualistic practices.’

After considering the evidence, the jury returned a verdict of guilty and Mary Townsend was sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment with hard labour. However, the jury added that ‘Rev. C. J. Walls ought to have been in the dock at the same time.’ The judge remarked, ‘that he hoped the press would take notice of the rider, and that the Treasury might be acquainted with the facts.’

What happened next? And what had the curate done to so offend public opinion and the Bishop of Rochester? What were the ‘ritualistic practices’?

Disturbing activities at St John’s

In the previous chapter we left the Rev Charles Joseph Walls in September 1894 in suspense, publicly humiliated after acting as a witness in Mary Townsend’s trial for begging. She was a member of an order, of which he was the ‘Father Superior’, set up to run two orphanages. Newspapers not just in Britain but all over the world had covered the story. The jury demanded that Charles also be put on trial for fraud. Lawyers claimed that he had left three positions as curate in disgrace and finally had his licence revoked by the Bishop of Rochester on the grounds of ‘ritualistic practices.’

We need to go back two years earlier – to 1892 – to the events which led to the trial.

Lambeth Palace Library contains a substantial file of correspondence between Rev Dr William J Strickland, Vicar of St Johns East Dulwich from 1888 to 1900, and the Diocesan Office of Randall Thomas Davidson, Bishop of Rochester, about Charles Walls and ‘ritualistic practices’ at St John the Evangelist, 1892-1893. The first letter in the file is from Dr Strickland following a visit to the Bishop on Tuesday 28 June 1892. He wanted to nominate Charles Walls, who had come to the parish on 20 April that year, as curate of St John’s. Charles had been ordained 3-4 years earlier in the Diocese of Ely and next worked in St Albans Diocese. Here, however, he had ‘quarrelled with the Vicar over assuming too great powers as Curate in charge of a District Church and advancing the Ritual beyond the Vicar’s wishes’. The Bishop of St Albans investigated, Charles admitted he was in the wrong and resigned his curacy. Charles then moved to be curate at Brent Pelham for a short period.

Lambeth Palace Library contains a substantial file of correspondence between Rev Dr William J Strickland, Vicar of St Johns East Dulwich from 1888 to 1900, and the Diocesan Office of Randall Thomas Davidson, Bishop of Rochester, about Charles Walls and ‘ritualistic practices’ at St John the Evangelist, 1892-1893. The first letter in the file is from Dr Strickland following a visit to the Bishop on Tuesday 28 June 1892. He wanted to nominate Charles Walls, who had come to the parish on 20 April that year, as curate of St John’s. Charles had been ordained 3-4 years earlier in the Diocese of Ely and next worked in St Albans Diocese. Here, however, he had ‘quarrelled with the Vicar over assuming too great powers as Curate in charge of a District Church and advancing the Ritual beyond the Vicar’s wishes’. The Bishop of St Albans investigated, Charles admitted he was in the wrong and resigned his curacy. Charles then moved to be curate at Brent Pelham for a short period.

Perhaps Strickland should have heard a warning bell at this point, but he felt sorry for the young man who seemed to be working hard and getting on well with parishioners. In addition he was in debt to the tune of £60 incurred from the expenses of his daughter’s illness. The curate’s stipend at St John’s was only £100 p.a. After serving eight months at St John’s, Charles was licensed as curate and there was no further correspondence in the file until the following year.

Nine months later, on 4 April 1893 Strickland wrote that there were major problems in the parish: he had learnt that Charles Walls’ wife had ‘gone over’ (become a Roman Catholic) together with their two small daughters, Gladys Philippa (5) and Ignatia Clara (1). The Churchwarden’s wife gave him a right dressing-down for this. His sermons were nconventional. Parishioners were becoming uncomfortable: Charles had admitted to one that ‘his heart and soul were in Rome’.

Acting on advice from the Bishop, Strickland wrote to Charles on 28 April: ‘I find your action in suffering your children to be subjected to a form of “second Baptism” and received into the Roman Church, added to many indiscreet statements in sermons and conversations during the last month has so completely shaken confidence in your loyalty to the English Church as to seriously injure your influence in this parish’ and reluctantly asked him to resign. Charles had been in the parish just over a year.

He refused to leave. Dr Strickland felt he had no option but to ask the Bishop to revoke the licence. The relationship deteriorated rapidly until a final breakdown in early May. By 9 May Charles appeared to have moved out of the family home (54 Fenwick Road) and was living at 18 Wildash (now Oglander) Road – his Vicar could not even find him! He then demanded 6 months stipend to quit.

On 12 May Charles himself replied to the Bishop with a rather confusing explanation in his defence. He said all had been well until the end of Lent that year. Had been left in sole charge of the parish for periods of 8 and 3 weeks and Dr Strickland had been satisfied with his work. He defended some of the ‘Roman’ criticism and said blessing of holy water, crucifixes, crosses and rosaries had all been with the Vicar’s sanction. He also claimed that his wife and children’s conversion to the Roman Catholic church had taken him by surprise!

Strickland called the accusations ‘a tissue of scandalous perversions’ and sent a formal reply to the Bishop of Rochester on 15 May requesting his Curate’s licence be revoked. He listed nine charges against him. Eight of these charges concerned Roman Catholic doctrine or practices and the supremacy of the Pope, but the ninth charge was ‘Contempt for Anglican Communion’ followed by ‘General Complaints’. This included his preaching, which changed when Strickland was absent ,and unreliability in carrying out his parish duties.

Sixteen letters of support were attached to the document. These came from parishioners, including churchwardens, and also neighbouring clergy. The letters included extracts from sermons perceived to have been preached in breach of Anglican doctrine. It appears that some of these sermons were delivered on dates when the vicar was absent from the parish.

On 31 May 1893 the Bishop of Rochester revoked the Curate’s licence.

A few weeks later on 9 August Dr Strickland had cause to write once again to his Bishop.

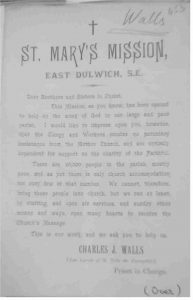

Though Charles Walls was still living in the parish and occasionally attending services he was also rumoured to have been received into the RC church (not yet true). He had been handing out leaflets for a St Mary’s Mission, having hired a ‘dirty little stable’ about 150 yards away from the church, and was about to start services – ‘schismatic services’ in Dr Strickland’s opinion. Though the Vicar really wanted

Though Charles Walls was still living in the parish and occasionally attending services he was also rumoured to have been received into the RC church (not yet true). He had been handing out leaflets for a St Mary’s Mission, having hired a ‘dirty little stable’ about 150 yards away from the church, and was about to start services – ‘schismatic services’ in Dr Strickland’s opinion. Though the Vicar really wanted

to avoid any further discussion on the subject, he felt obliged to state briefly from the pulpit th at as his licence had been withdrawn Charles Walls ‘was unauthorised to conduct any religious service or meeting in the parish’. No-one from St John’s ever attended St Mary’s Mission.

at as his licence had been withdrawn Charles Walls ‘was unauthorised to conduct any religious service or meeting in the parish’. No-one from St John’s ever attended St Mary’s Mission.

The Bishop of Rochester sent a stern letter (hand-delivered by Strickland) to Charles to ask him to desist ‘officiating without the consent of the incumbent of the Parish or the Licence of the Bishop of the Diocese’ otherwise he would be guilty of an Ecclesiastical Offence.

Suddenly the situation changed. On 25 November Strickland wrote that he had met Charles Walls the previous day who said that he had closed the Mission as he had ‘awakened to a sense of his sin’. He wanted to make public apology in church (which was refused). He had not yet been received into the Roman Catholic church as he refused to renounce his orders. Strickland would only offer his personal forgiveness and refer the matter to the bishop.

On 7 December the Bishop interviewed Charles Walls, by now living at 28 Nunhead Lane, the address of his schoolmistress sister, Maria Theresa Walls. A few weeks earlier his wife’s mother had died and the legacy gave them ‘enough money to make them independent of clerical work’.

As a result he had closed the Mission and desired reconciliation with the church. He asked the Bishop for a general ‘Leave to Officiate’ in the Diocese. This was out of the question, and it was suggested that he find an incumbent, tell them everything, and see if he could work on probation as curate – preferably in another Diocese. The Bishop concluded: ‘I agreed with Mr Walls that it would not be easy to obtain such a post either in this Diocese or elsewhere but I represented that the fault was entirely his own and that I could not be responsible for extricating him from the position in which he had placed himself. He did not inspire me with confidence.’

St John’s Church today

The final letter in the file, dated 16 December 1893, was to Dr Strickland from the Rev Charles Cuthbert Naters, Curate of Dunmow Parish Church. He wrote: ‘The Rev C J Walls has replied to an adv[ert] for help Dec 24-31. I understand that he has been until latterly with you. May I trouble you whether you know if he is a fit and proper person to take duty.’

The answer is unknown, but one strange aspect to the whole saga is that there is barely a mention of the events in St John’s archives. In one letter Strickland comments that there was no need for the Vestry Meeting to discuss events. A report of the subsequent trial in Reynold’s Newspaper hinted that questionable activities had taken place at St John’s.

Mr Torr—Did the sacristan make a complaint with reference to a young lady? Witness—Yes, but the vicar was very much in love with the particular young woman. (Loud laughter.)

‘The Curate said there was no truth in the suggestion of immorality at St. John’s Vestry; he received ladies for confession . . . Addressing the jury, Mr Torr criticized the rev gentleman’s evasions and the “cowardly charge” he had tried to make against his late Vicar.’ The treatment he had received from Dr Strickland clearly still rankled.

Within weeks Charles had started his final Peckham project, the one which was to lead to his court appearance. In February 1894 he rented 42 Elm Grove in Peckham. The Landlord thought this was for use as a private dwelling as he would not have let it had he known it was for an institution as he told Mr Walls at the time ‘he objected to children’. The begging offence took place in July.

I cannot find any reference to further legal action which suggests Charles avoided imprisonment; otherwise the newspapers would certainly have reported it. Personally I think he was probably sincere in the work he was attempting to do rather than committing fraud.

At the end of 1894 Charles Joseph Walls was formally and finally received into the Roman Catholic church in Coventry by the Rev A. A. Pereira, O.S.B.

In the 1901 Census he was in Lambeth with his wife and daughters, had had a career change, and was now a tea merchant. After a short period of work with the Converts’ Aid Society **, he had, with its help, started in the business in which he was engaged up to the time of his illness about a year before his death. In 1902 a son, Ivo De-Maria Whitmore, was born. The family finally moved to 13 Abbeville Gardens Clapham, where he stayed until his death, aged only 53, on 19 December 1914.

A Requiem Mass was said on 22 December by the Very Rev John Bennett, CSSR, at St Mary’s RC church, Clapham, and he was buried in Brompton Cemetery. His obituary was published in the pages of The Tablet mentioning his roles at Luton and Brent Pelham – though not at East Dulwich.

Christine Camplin

(with thanks to Clare Brown, Lambeth Palace Library)

** The Converts Aid Society was set up in 1890 to help former non-Catholic clergymen and nuns who became Catholics, and as a result faced unemployment and homelessness. It is likely that CJW turned to them for assistance in 1894.

Christine Camplin

Sources

New York Times, 23 August 1894; bit.ly/PSN146p21d

The Tablet, 25 August 1894; bit.ly/PSN146p21a

South Wales Echo, 14 September 1894; bit.ly/PSN146p21c

The Guardian, Wednesday, 19 September, 1894

The Advocate (Melbourne, Vic.) 3 November 1894; bit.ly/PSN146p21b

Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1894

Davidson; 36 – Correspondence 1893, Southwark – Rev. C.J. Walls

South London Press, 01 September 1894

Reynold’s Newspaper, Sunday 16 September 1894

The Tablet, 26th December 1914, Page 29; bit.ly/PSN147p14a

Converts to Rome since the Tractarian movement to May, 1899. William James Gordon-Gorman (London, 1899); bit.ly/PSN147p14b

Reprinted from Peckham Society News, Issue 146 (Autumn 2016 and Issue 147 (Winter 2016)