The Princes and the Prodigy

In 1860 Victory Cottages, Peckham, was a small row of eight cottages on Bedford Street, now called Sandison Road. Today Jack Jones House stands on the site. Newspaper adverts for the freehold described: ‘genteel cottages, commanding the best class of tenants for such sized houses’. They offered a respectable home with ‘plenty of town water and well-drained gardens front and rear’, ‘a healthy situation’, ‘pleasantly situate’. Each house contained four rooms (two parlours and two bedrooms) and a wash-house. Rent for a cottage was £15 pa or 6s. (30p) per week.

In 1860 Victory Cottages, Peckham, was a small row of eight cottages on Bedford Street, now called Sandison Road. Today Jack Jones House stands on the site. Newspaper adverts for the freehold described: ‘genteel cottages, commanding the best class of tenants for such sized houses’. They offered a respectable home with ‘plenty of town water and well-drained gardens front and rear’, ‘a healthy situation’, ‘pleasantly situate’. Each house contained four rooms (two parlours and two bedrooms) and a wash-house. Rent for a cottage was £15 pa or 6s. (30p) per week.

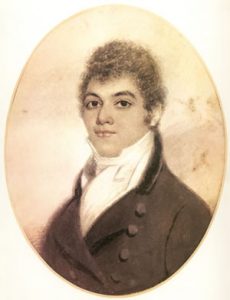

No one knows why George Bridgetower, the acclaimed violin prodigy and friend of Beethoven, was living in Peckham when he died in the end cottage in February 1860. He had led an extraordinary life and it is only fairly recently that parts of his story have been revealed. Much still remains a mystery.

George was born in Biała Polaska in Poland on 13 August 1778 and baptised Hieronymus Hyppolitus de Augustus in the town church on 11 October. His father, John Frederick (aka Joanis Fredericus de Augustus), probably came from Barbados. George’s mother, Maria Ursula (née Schmid) was German.

Soon after George’s birth, the family moved to Eisenstadt, Austria, where a second son, Frederick, was born in about 1782. John Frederick became a valet in the household of Prince Esterházy. The children were fortunate: the Esterházy family had hired Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) as Kapellmeister in 1761. Haydn spent over thirty years in service to this family as director of music at their two palaces at Eisenstadt and Esterháza in Hungary. His responsibilities included Masses and court music, composition, running the orchestra, playing chamber music for and with his patrons, and operatic productions, both human and marionette. There was an orchestra, opera house and a puppet theatre. John Frederick may have asked for music lessons for his older son, but Haydn would soon have recognised and encouraged a gifted child. Later concert adverts described George as Haydn’s pupil, though John Frederick left Esterházy service when the child was only about seven.

It was long believed that George’s first public concert was in Paris in April 1789. However, he features in an advertisement for a concert in Frankfurt three years earlier.

Hieronymus August Bridgetown, son of a Moor and former valet to his Most Serene Prince Esterházy, 7 years old, a pupil of the worthy Haydn, who had the favour of playing before his Majesty the Kaiser, as well as in various Princely courts to universal applause, will have the honour, on Wednesday 5 April here in the Concert Room of the great Red House, to give a grand instrumental concert, in which he will perform on the violin, in anticipation of warm encouragement for it from an honourable public.

Frankfurter Frag- und Anzeigungs-Nachrichten, 4 April 1786.

For this first appearance John Frederick added ‘Bridgetown’ to the family name. (The later spelling of Bridgtower or Bridgetower was inconsistent even during his lifetime.)

The family moved on to Mainz, a flourishing musical centre. They may have been encouraged by Ernst Schick, Chamber Virtuoso and first violinist to the Prince-Elector and Archbishop of Mainz, who probably also tutored the young George.

In 1788 George and his father embarked on a Mozart-style European tour. Maria, his mother, stayed in Mainz with the younger boys: a third son, Johannes Albertus Bridgetown had been baptised there on 1 March 1787. Between December 1788 and March 1789 George performed in Germany, Liege, Brussels and the Hague, and on 11 April 1789 appeared at the Concert Spirituel in Paris, an occasion described at the time as the: ‘Début de Mr. Georges Bridgetower, né aux colonies anglaises, âgé de 9 ans.’ (Another name change: he was now advertised as George Frederick Augustus Bridgetower – by a strange coincidence the Christian names of our Prince of Wales, the future George IV.)

As conditions in France became unstable with the start of the Revolution in May the Bridgetower tour moved on to England. An account in the Bristol Journal of 22 August 1789 describes George playing in Brighton at the time of the Prince of Wales’ birthday that month. It is likely that John Frederick had approached the Prince of Wales for help in promoting his son. The Prince of Wales was a patron to many artists and musicians who came to his court from all over Europe. In 1787 he commenced construction of the Royal Pavilion at Brighton as a summer seaside retreat. On 25 September George was presented to their Majesties and the Princesses at Windsor Lodge.

Royal presentations did not pay the bills, however, so in November father and son moved on to the winter season at Bath at the invitation of the celebrated Italian singer and friend of Haydn, Venanzio Rauzzini (1746-1810). The boy took the city by storm: 550 guests attended his first concert at the Assembly Rooms on 5 December. On Christmas Eve George played a ‘a concerto’ between the second and third parts of Handel’s Messiah as a benefit concert for Rauzzini. There were two further concerts at Bristol Assembly Room on 18 December and New Year’s Day. It was said that he earned 200 guineas for a single appearance and some tickets sold for £5.

The amateurs of music in this city received on Saturday last at the New Rooms the highest treat imaginable from the exquisite performance of Master Bridgetower, whose taste and execution on the violin is equal, perhaps superior, to the best professor of the present or any former day. Those who had that happiness were enraptured with the astonishing abilities of this wonderful child – for he is but ten years old. He is a mulatto, the grandson, it is said, of an African Prince. The greatest attention and respect was paid by the nobility and gentry present to his elegant Father, who is one of the most accomplished men in Europe, conversing with fluency and charming address in its several languages.

The Bath Journal, 7 December 1789

John Frederick managed – or rather, manipulated – his son’s career. He was skilled in public relations, variously claiming to be an African prince, an Abyssinian from the West Indies or the son of an Indian princess. He dressed extravagantly, often wearing Turkish robes, the fashion of the time.

With Bath at his feet it was time to launch young George on London. A small private event on 23 January 1790 was followed by a repeat of the Messiah performance at Drury Lane Theatre on 19 February. Further concerts ensued.

Meanwhile there were growing issues with the behaviour of George’s father. It was no longer interesting; he was alienating people with his officious attitude and there were rumours of gambling debts and eventually some form of nervous breakdown. As a result, in April 1791 the Prince of Wales gave him travel expenses to return to his family, now in Dresden, and took 12 year old George under his personal Royal protection. The Prince oversaw his general schooling and musical education. This included violin lessons with François-Hippolyte Barthélémon (long-term orchestra leader at the Royal Opera) and Croatian violinist Giovanni Giornovichi (Ivan Jarnovic), and composition with Thomas Attwood, organist at St Paul’s and professor at the Royal Academy of Music.

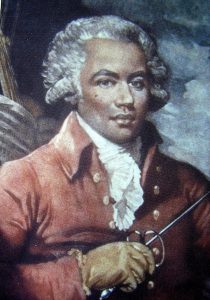

George met many other musicians in the Prince’s circle including the violinist and composer Giovanni Battista Viotti (described as the greatest classical player of his day), and composer Samuel Wesley (1766-1837). He probably also met Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745-1799), the first known classical composer of African ancestry, born to a Guadeloupe plantation owner and an African slave girl, educated in Paris, and a renowned violinist, composer – and swordsman. He came to England in 1787, and then in 1789-1790 fled the Revolution with his patron Philippe, Duc d’Orléans. He gave musical performances and demonstrations of swordmanship in London.

George was now established as a professional musician and a leading member of London’s artistic community. He had had no childhood; the life of a child prodigy must have been a strange and lonely one. He became one of the first violinists of the Prince’s private orchestra who divided their time between the London residence (Carlton House) and Brighton, and held the post of first violinist for 14 years. In addition to work stemming from the Prince’s patronage he took a variety of freelance jobs, performing in around 50 concerts in London theatres, including Covent Garden, Drury Lane and the Haymarket Theatre, between 1789 and 1799. On 28 May 1792 he played a concerto by Viotti in a concert given by Barthélémon at which Haydn also performed.

George took part in a novel entertainment on 31 October 1793 at King’s Arms in Cornhill given by Charles Claggett, ‘Harmonizer of Musical Instruments’, and featuring Claggett’s ‘Aiuton, or Ever Tuned Organ, an instrument without Pipes, Strings, Glasses or Bells, which will never require to be retuned in any Climate’.

In 1802 George obtained leave to visit his mother in Dresden and gave concerts there on 24 July 1802 and 18 March 1803. They were so successful that, having obtained an extension of leave, he went to Vienna in April 1803. A permit to travel, dated 27 July 1803, gives a description of the young man: ‘George Bridgetower; character, tonemaster; born in Viala, Poland; twenty-four years of age, middle height, smooth brown face, dark brown hair, brown eyes and somewhat thick nose.’

Knowledge of his skill and Royal connections had preceded him and in Vienna he was introduced to Beethoven who had already begun work on the first two movements of what was to become the Sonata for Pianoforte and Violin in A (Op.47), the ‘Kreutzer’ Sonata. It was barely finished in time for the première on 24 May 1803 at the Augarten-Halle in Vienna. Beethoven himself played the piano. There was no rehearsal and parts of the work were still in manuscript. George made a change to his part to the delight of the composer who presented him with his own tuning fork, which is now housed in the British Library.

Beethoven also wrote an affectionate dedication in Italian to his friend on the manuscript, translated as: ‘Mulatto sonata composed for the mulatto Bridgetower, great fool and mulatto composer’. Unfortunately, soon afterwards George insulted the reputation of a woman whom Beethoven knew so the composer crossed out his name and rededicated the work – and thus all future printed copies – to the French violinist Rodolphe Kreutzer.

Kreutzer was later said to have declared the piece impossible to play and never performed it in public.

George returned to London after visiting relatives of his mother in Poland. His younger brother, Frederick, joined him in London and they performed together at a concert in the New Rooms, Hanover Square, on 23 May 1805. (Frederick Bridgetower (1782-1813) later moved to Ireland and married Elizabeth Guy in 1808. He taught ‘cello and piano, composed, organised and performed in concerts at the Rotunda, Dublin.)

On 4 October 1807 George was elected to the Royal Society of Musicians in London, and then went up to Trinity Hall, Cambridge University. He was awarded the degree of Bachelor of Music on 28 June 1811. His undergraduate exercise was an anthem to words by the poet F.A. Rawdon, and was performed before the Chancellor of the University with full orchestra and chorus at Great St Mary’s Church on 30 June 1811. It was played again in 1847. (The college has named a conference room after him.) During this period George taught the piano, and in 1812 he published a piano piece, Diatonica Armonica, dedicated to his pupils.

After returning to London he played in the Philharmonic Society’s first season in 1813 and was recommended for membership. He resigned his membership to travel abroad, later applied for readmission and was readmitted on 6 November 1819. The Secretary of the Philharmonic Society wrote in support:

George Bridgetower is one of our greatest musical assets. He is approaching 40 now, and is adored by his pupils, highly respected amongst other musicians and continues to play the violin and piano beautifully. We recommend that he is allowed permanent membership of the Philharmonic Society.

George Bridgetower married Mary Leech Leake on 9 March 1816 at St George’s, Hanover Square, London. She was a wealthy young woman in her own right. They had two daughters: Julia, born 28 November 1817, who died the following summer, and Felicia, baptised 18 July 1819 in Ewell, Surrey. The family address was given as Upper Seymour Street, Portman Square, and father’s occupation the rather unspecific ‘Gentleman’.

The marriage hit problems and by 1824 Mary was living in Rome with daughter Felicia. Felicia returned to England to marry Louis (Luigi) Philippe Baldersar Mazzara on 4 September 1839 at St George’s, Hanover Square, and then went back to Italy where two sons were born. Mary Bridgetower died in Italy in 1835.

Around the time of his marriage George ceased performing in public. After 1820, apart from brief visits to England, he mostly lived abroad. There is no suggestion that he had become a recluse: he continued to teach, write to, and visit his musical acquaintances. Surviving correspondence shows the respect he enjoyed amongst his peers. He was fluent in English, German, French, Italian and Polish. Letters show him in Rome (1825 and 1827), London (1843 & 1846), Vienna (1845), Vienna and Paris (1848). He also visited his daughter in Italy. Friends included musicians from a wide range of fields: Camille Saint-Saëns, Thomas Attwood, Johann Cramer, Vincent Novello and Samuel Wesley.

Sadly one consequence of retiring from life in the spotlight is that the public eventually forgot George Bridgetower. It was widely believed he had died in England in the 1840s or 1850s until Frederick George Edwards, Editor of the Musical Times, tracked down his death certificate ‘through a curious chain of clues’ (unspecified) in 1908. However it was also Edwards who declared that he had ‘come down in the world’, dying in a ‘back street at Peckham’.

His death certificate records that ‘George Polegreen Bridgetower, Gentleman’, died at 8 Victory Cottages on 29 February 1860 aged 78 years. Cause of death, certified by a doctor, was ‘Synocha 10 days Calculus of long standing’ (synocha = fever). The informant was Ann Chapman of Neptune Cottage, Park Street, Camberwell. Much has been made of the fact that she was illiterate. She misspelt Polgreen and made an error in his age (he was actually 81). Ann, a widow aged 52, lived with her daughter and son-in-law Emma and William Wakeman, a greengrocer. She may have been employed as a private nurse.

Edwards then searched for a burial place. He drew a blank with local cemeteries and eventually found George had been buried in Kensal Green Cemetery, nearly ten miles away, ‘that great Valhalla of literary and musical celebrities’, on 7 March 1860.

Edwards then searched for a burial place. He drew a blank with local cemeteries and eventually found George had been buried in Kensal Green Cemetery, nearly ten miles away, ‘that great Valhalla of literary and musical celebrities’, on 7 March 1860.

His tombstone simply reads:

GEORGE POLEGREEN BRIDGETOWER ESQre

DIED 29th FEB 1860 AGED 78 YEARS.

On 10 September 1859, a few months before his death, George had made a will leaving his entire property not to his daughter but to his wife’s sister, Clara Leech Leake Stuart in Scotland. He gave his name as ‘George Polgreen Bridgetower, of Peckham,’ followed by the words ‘being about to go to Paris.’

George did not die friendless. The executor of his will was Mr Samuel Appleby, of No. 6, Harpur-street, Red Lion-square, Holborn. Appleby was not only a solicitor but an amateur violinist who owned his own 18th century Guarnerius violin. He sold the estate through the auction company Puttick & Simpson on 30 June 1860: it included two violins by Antonio Stradiuarius, a violincello, a viola and a box of Musical Glasses raising less than £1000 (worth upwards of £120,000 today). So – after his death George’s friends had swiftly arranged transport to and burial in Kensal Green (rather than Nunhead Cemetery), wound up the estate, and organised a tombstone. This was no lonely pauper’s funeral.

There is a very odd, unsourced and undated reference in LaBrew, who also described Kensal Green Cemetery as in ‘Peckham’:

‘According to documents at Peckham: I have just buried a certain George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower, age 81, in Kensall Green Cemetery. I knew him a little. He lived a quiet life in Peckham, but had the manners of a gentleman. Rumour has it that he was once a famous violinist, performing for the Prince Regent, and counting Beethoven as a close friend. I find that hard to believe; he seemed almost penniless, although he left £1000 to his sister-in-law. [Signed Mr. Mort]

But why did George choose to come to Peckham in the 1850s? At that date the location would have had two advantages: it was still a semi-rural area, surrounded by market gardens, and had swift and easy access to central London as Tilling’s ran regular daily horse buses between Peckham and Oxford Street. From there he could catch a railway train to Dover and the continent.

George Bridgetower decided to drop out of the limelight in his mid-30s. Maybe he wanted a more quiet life. He lived to his 80s, and kept up an active correspondence with his peers.

Mozart died at the age of only 35, but is famed to this day for his compositions. Few of George’s compositions have survived, and some have since been attributed to other musicians. Three works ‘composed by an African’ are now known to be by Ignatius Sancho.

But did he deserve to be forgotten? Or was he a child prodigy who never fulfilled his promise? It would be a tragedy if George Bridgetower’s main claim to fame today was the colour of his skin , particularly since, as far as can be judged from contemporary reports, it was cause for comment but did not detract from his acclaim.

I believe he deserves wider recognition for several reasons:

- an outstanding musician, not just as a child prodigy but in adulthood;

- the son of a palace servant who went on to consort with princes and the leading musicians of the day;

- the obvious esteem in which he was held by his peers, standing as an equal with the musical community of his time.

An accurate and complete biography is long overdue to fill in the gaps, correct the false recycled information and remove the inventions – many of which were created by his father to promote his early performances.

Christine Camplin

Reprinted from Peckham Society News, Issue 161 (Summer 2020)

William Hart. ‘New Light on George Bridgtower’ in The Musical Times Vol 158 (1940), p.95-106, September 2017

Arthur R. Labrew. Some Omitted Items about George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower, violinist and his brother Frederick Bridgetower, violoncello. (c.2015) (http://www.kresgeartsindetroit.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/George-Augustus-Polgreen-Bridgetower.pdf)

F. G. Edwards. ‘George P. Bridgetower and the Kreutzer Sonata’ in The Musical Times, Vol. 49, No. 783 (1 May, 1908).

Black Europeans: A British Library Online Gallery feature by guest curator Mike Phillips (https://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/features/blackeuro/bridgetowerbackground.html)